by Giuseppe Di Bella, artist/photographer based in London

Art and myself vs. the British anti-terrorist branch and the FBI

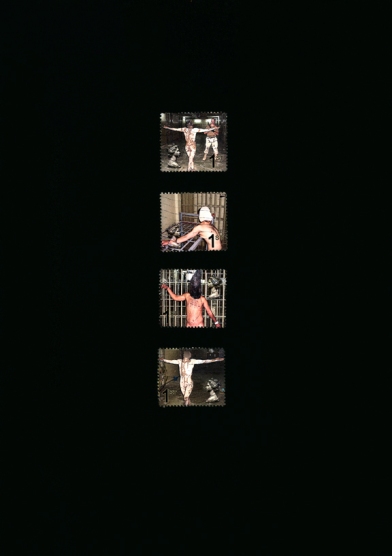

The first time I saw the Abu Ghraib photographs I was unsure what I was looking at. Of course I very soon realised the seriousness of these images and their global impact upon political, social and cultural life. In the same way that many of us were, I was deeply disturbed and shocked by these images as they contrasted with the US military and political objectives under George W Bush presidency. These objectives were to bring democracy to the people of Iraq and to free them from the tyranny of its former president, Saddam Hussein.

Although the Abu Ghraib images provoked profound anger and disgust, I must admit they didn’t really come as a surprise. Sadly, these atrocities happen in every single war and are nothing new. I believe the Abu Ghraib photographs expose and remind us of the power relation in a war zone. An imbalanced power: the powerful against the powerless.

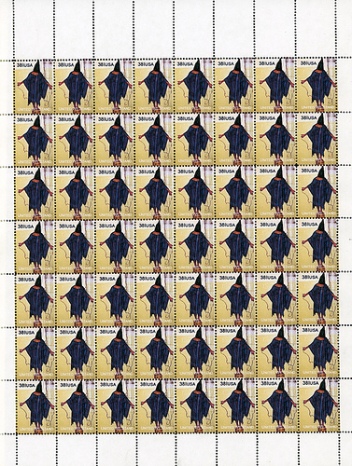

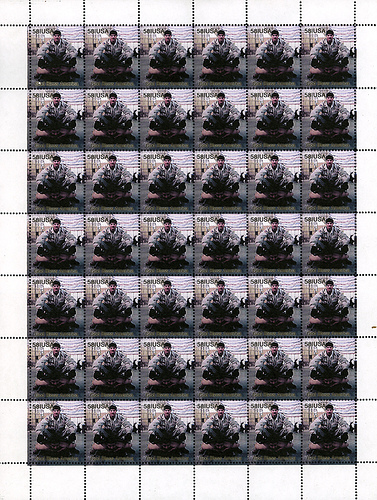

As an artist working with photography, I felt I had a moral obligation to respond to the Iraqi conflict and particularly to these tragic events. At the time (May 2004) I had concerns on the way public images were being circulated, treated and consumed by society; particularly gruesome and violent images. So it is from this perspective that I produced the Abu Ghraib series that consist into a collection of postage stamps that I put into public and global circulation. (Make it a better place – Group exhibition conceived and curated by Dinu Lee – The Holden Gallery – MMU)

The reasons I chose the postage stamp format as a vehicle for my ideas was because of its consumable, desirable and collectable characteristics. It is also a very democratic way to diffuse images and information. Traditionally, the postage stamp function is to pay tribute or commemorate the traditions and culture of a country. It is also a powerful form of communication as it travels around the globe advertising the proudest aspects of a nation, in contrast to the Abu Ghraib photographs. I was interested in how the mechanical act of licking and stamping a postage stamp could be linked to a notion of humiliation and abuse/torture as revealed in the photographs. I was conscious that this process could turn the viewer into an active consumer and make the user aware of the consumption and treatment of public images in circulation. This could also lead the user to become an active accomplice – in some sense – to the abuse and violence. The repetitions of images on the stamp sheets are also a reflection of the depersonalisation that happens to victims of such abuse. The intimate and personal details of each account, and the consequences for the abused/tortured is hidden and forgotten as the images are multiplied, repeated and ‘consumed’ by society.

The way I chose to present the work was also a very important factor, as I wanted the viewer to look at the stamps as objects of consumption. In addition, four series of franked stamps – therefore used/consumed – are presented framed and as such, as trophies. Ultimately, that is what some photograph seems to be about. Through this presentation, I wanted to highlight the contemporary society’s appetite to consume such gruesome and violent imagery.

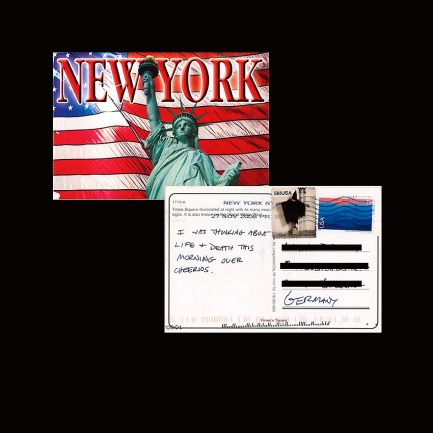

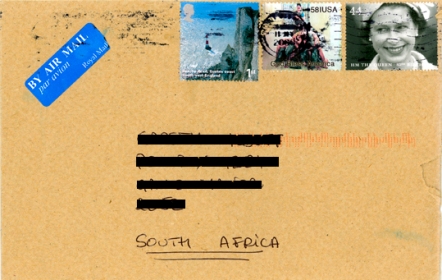

As there is two version of the Abu Ghraib stamp (US/UK) I had to delegate the distribution of the US version of the stamp to a friend who lives in New York: Art. (Stands for Arthur) My friend Art, whom I have not met (not yet!), agreed to actively participate in this project. I sent Art, via an international courier company (I won’t name it here for legal reasons) more than 100 envelopes and postcards – all pre-addressed and with the Abu Ghraib faux stamp affixed on it. The instructions given to Art were clear: to buy US stamps and affix them onto the envelopes and postcards beside the faux stamp and to post them from New York.

When I contacted the courier company to inquire the lateness of the parcel I was told that the police, then subsequently the British anti-terrorist branch were investigating the content of the parcel for alleged ‘anti-American documentation’. I was also informed that the content of the parcel had been scanned and passed onto the American authorities for further investigation. I requested the courier company many times during that week to be contacted by the British authorities in order to explain my work, but my requests were systematically refused.

A week later, I required the courier company either inform the British authorities to release the parcel or to charge me with an offence I evidently had not committed, (The fact that I use a real postage stamp onto the envelopes and postcards, invalidated the potential problem any faux stamp could present to the postal authorities) The courier company agent put me on hold and eventually informed me that the British authorities found the work ‘offensive’ to which I replied that the images are indeed unpleasant; but they are a verification of the sexual abuse and of the torture to the victims, their families and their communities. They are an insult to humanity and human dignity. So, I cannot but agree with the British and other authorities that the images are indeed offensive. Later, I was also told that the British authorities could keep the work indefinitely, to which I answered that it was illegal even for the British authorities to hold something indefinitely, particularly when no offence had been committed. I demanded the immediate release of the parcel otherwise I would be seeking legal action to retrieve it. Eventually, the following day the parcel left for its final destination in New York. My friend Art started to post the mail and I was beginning to receive back the envelopes and postcards so important for my installation.

A few weeks after the British authorities incident, I received a phone call from my friend Art informing me that two FBI agent were about to pay him a visit regarding the Abu Ghraib work and myself. As he was obviously concerned about it, I suggested he simply answers their questions and not to worry too much, as it was clear they were inquiring about my artwork and me. The FBI wanted to know where he knew me from, if I had spoken to him about my political views and finally if I had a bigger agenda. (Making new stamps maybe?) The funniest thing about this laughable story is that the two FBI agents were dressed with back suites and black glasses.

After that, I did not hear neither from the British authorities or the FBI. Although I freak out about the British anti-terrorist branch, the FBI seemed to be less formidable because of the comical link inferred by their attire. Sometimes I wonder how much trouble I would have got into if I were a Muslim artist, or worse if was living in America?

The saddest thing during and about this story is that I was beginning behaving as if I were doing something wrong, something illegal. I felt my emails and my phone calls were being monitored. Some how I felt watched. Whether this was pure paranoia or not, I don’t know. The idea of being investigated by the anti-terrorist branch was somehow concerning, and although I am an Italian citizen, I could be easily mistaken for a person of Middle Eastern origin, therefore a potential threat to the authorities – or am I wrong? The reality remained that I had to bring the framed work abroad without having it seized by the authorities. I wasn’t prepared to take any more risks, because of the exhibition deadline, and little by little and with the crucial help of my friends, the installation material crossed the British border unnoticed and the work was successfully exhibited in Brussels. (Portraits de l’autre – Group exhibition curated by Virginie Devillers – Musee d’Ixelles, Brussels – Belgium)

The story of the Abu Ghraib series inevitably points to the events of the 9/11 and the Madrid and London bombings and their aftermath. Anti-terror laws have been implemented all over the world. We must wonder whether these new laws pose a threat to our freedom of speech and artistic expression and if they infringe our civil liberties. We need to ensure that the current war on terror does not completely annihilate our freedom; it should not justify everything and anything. More power is being taken from us when actually more trust should be given to people. The experience I have encountered with the authorities poses a fundamental question: Are we really living in a democratic society?